Since April at the Camp of the Sacred Stones, land and water protectors of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe have stood in opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). In recent weeks the camp has swelled to thousands as members of other indigenous communities and anti-pipeline activists have rushed to the area to stand with those opposing the pipeline.

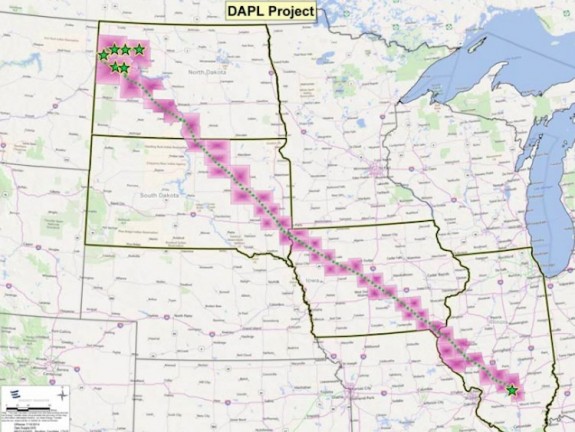

The DAPL is a 1,172 mile long oil pipeline that would transport 470,000 – 570,000 gallons of crude oil every day from the oil fields in North Dakota to an oil refinery in Illinois. The route takes it across North and South Dakota, Iowa, and Illinois, and would cross the Missouri River. Twice.

The pipeline project is being headed by a Texas-based company called Energy Transfer Partners, whose subsidiary is Dakota Access LLC. Phillips 66 is also an investor in the project, and as of this summer the pipeline giant Enbridge acquired 49% of the project. Energy Transfer Partners already owns 61,000 miles of pipeline, and has been responsible for numerous pipeline leaks, many of which come from its subsidiary Sunoco. Enbridge, which has been targeted by anti-pipeline activists for years across the Midwest, was responsible for 804 spills between 1999 and 2010. These spills included the largest and costliest pipeline spill in U.S. history into the Kalamazoo River, spilling nearly 1,000,000 gallons of oil.

Pipelines leak frequently and the damage they cause to ecosystems and communities is unacceptable. In fact, a 2012 study showed an average pipeline had a 57% probability of experiencing a major leak with up to $1,000,000 in damages. The study further documented 1,337 “unintentional releases” between January 1, 2010 and July 7, 2012.

This proliferation of pipeline infrastructure construction not only infringes on indigenous treaty rights (Fort Laramie Treaty 1868), it is also thought to be in violation of Federal law (including the completion of a full Environmental Impact Statement). Members of the Sacred Stone camp believe that this pipeline construction puts communities at risk. Communities and ecosystems have already been put at risk as a consequence of fracking in Northwest North Dakota.

So why has CURE been following this story?

CURE’s history is tied to protecting the Minnesota River and the communities that depend on it. A threat to clean water anywhere is a threat to clean water everywhere. Could you imagine how we in the Minnesota River Valley would react if this pipeline were being built under the Minnesota River putting communities at risk?

If such a pipeline was built and it leaked, imagine the consequences. And problems associated with a spill wouldn’t necessarily disappear after cleanup from a spill. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has been studying the site of a spill in Bemidji, since 1979.

“After initial cleanup, about 110,000 gallons of crude oil remains in the subsurface. This site thus provides a unique opportunity to study a contaminant plume where the location, amount, and timing of the spill are precisely known. The study focuses on how crude oil spreads in soil vapor and groundwater.“

The standoff is not only happening in the fields of North Dakota but in the courtroom as well. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe have filed suit against the Army Corps of Engineers for their permitting process, claiming that risks to their community were ignored. At an August 24th hearing a judge declined to issue a decision until Sept. 9th. Until the 9th work has ceased at the site of the protest. Farmers in Iowa have also filed suit against the project, claiming that the Iowa Utilities Board issued permits outside of its jurisdiction. The farmers argue that the Board’s application of eminent domain could only be legal if the pipeline was considered a public utility. Akin to members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and those opposing the pipeline, many farmers believe a pipeline across farm country would pose a serious risk to farmers’ income and way of life.

No energy development, no matter what the form, should come at the expense of the environment and communities. All development has risk and associated costs, requiring our strategies and decisions to be prudent, conservative, and with the consent of the communities most affected.

Clean water, clean air, and our communities must be protected at all costs.