This is the third part in a multipart series called Groundwater 101. Groundwater 101 provides the foundation for a good working understanding of groundwater—the source of drinking water for 75% of Minnesotans. There are three goals of this blog series: first, to introduce the basic science behind groundwater; secondly, to explore the impacts that agriculture can have on groundwater, especially in and around the Minnesota River Watershed; and thirdly, to summarize the role that government policies and agencies play in shaping our groundwater resources. Happy learning!

In the first two installments, I did my best to explain the basic rules of groundwater behavior, and it may have seemed like little more than a groundwater geek-out for a pseudo-scientist. However, the fact of the matter is that these basic rules are the basis for understanding why and how groundwater affects us as water drinkers and water users. While the full range of impacts are many and varied, this is a cursory introduction to them and how they may vary from one groundwater province to another.

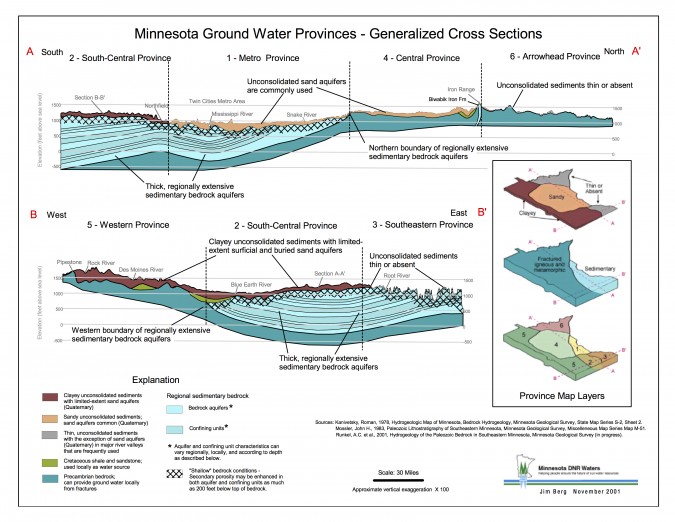

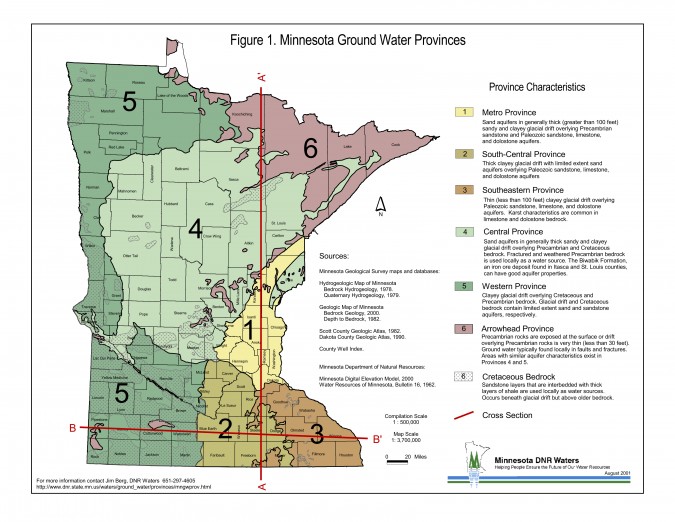

Throughout, try to keep in mind the following two images. Use the map of the groundwater provinces below to help you locate yourself and the groundwater resources under your feet. Also consider the cross-sections, which show how the layers of geology stack on top of each other.

Surface Water Levels

A healthy water system with good groundwater recharge moderates water levels for surface water bodies like rivers and lakes. Our reputation as the Land of 10,000 Lakes is thanks to some pretty awesome groundwater, and we can’t forget that. The reason groundwater is so critical to keeping rivers flowing and lake levels up, even when there is no rain, is that it moves so slowly.

A healthy water system with good groundwater recharge moderates water levels for surface water bodies like rivers and lakes. Our reputation as the Land of 10,000 Lakes is thanks to some pretty awesome groundwater, and we can’t forget that. The reason groundwater is so critical to keeping rivers flowing and lake levels up, even when there is no rain, is that it moves so slowly.

Spring is naturally a time for groundwater recharge in Minnesota because there is significant rain and snowmelt, but fewer plants and cooler temperatures mean that evapotranspiration is down. So extra water soaks into the ground, joins the groundwater, and begins the slow journey “downhill” to the nearest surface water body. However, because groundwater travels so slowly, this may take weeks or months, so the spring rains that travel via groundwater arrive at their destination long after the rainfall. Thus, in summer, when hot temperatures and dry spells may stress water bodies, spring rain is still flowing into lakes, rivers, and streams. In some cases, this protects habitat for trout and other aquatic life by keeping streams cool and deep, even in summer. It can also just make a water body better for recreation by keeping water levels high enough for canoeing, boating, or swimming in hot summer months.

When groundwater recharge is interrupted, either by artificial drainage or impervious surfaces brought by urbanization, and run-off at the time of rainfall increases, the result is highly fluctuating water levels instead of a natural moderation of flow.

When groundwater recharge is interrupted, either by artificial drainage or impervious surfaces brought by urbanization, and run-off at the time of rainfall increases, the result is highly fluctuating water levels instead of a natural moderation of flow.

In Provinces 1 and 4 in Central Minnesota, where the surficial deposits are sandy, groundwater recharge is easy. In Provinces 2 and 5, with surficial clay that tends to infiltrate precipitation much more slowly, it becomes even more important to conserve soil structure either by practicing soil-friendly agricultural practices or by planting deep-rooted native plant species. Both of these practices create channels in the clay that allow water to infiltrate this material despite its low permeability. In Province 3, the exposed stripes of permeable bedrock tend to readily recharge groundwater and carry it to deep bedrock aquifers.

Contamination

While places that readily absorb groundwater recharge may seem to be the best place to be, there’s a flip side to this coin. Those same places are the places where contamination spreads the fastest. Since 75% of Minnesotans rely on groundwater as their drinking water, the nature of the spread of groundwater contamination is extremely important.

In some ways, water traveling through an aquifer is naturally filtered, either through the natural breakdown of contaminants over time, or because pollution gets caught on the surface of the rock as the water moves through it. For this reason, groundwater has often supplied safe drinking water with little need for treatment–one of the reasons that, as the Twin Cities metro area population has expanded, the use of groundwater as a source of drinking water has outstripped the use of surface water.

In some ways, water traveling through an aquifer is naturally filtered, either through the natural breakdown of contaminants over time, or because pollution gets caught on the surface of the rock as the water moves through it. For this reason, groundwater has often supplied safe drinking water with little need for treatment–one of the reasons that, as the Twin Cities metro area population has expanded, the use of groundwater as a source of drinking water has outstripped the use of surface water.

However, the efficacy of an aquifer in acting as a filter depends largely on how quickly the water moves through it. Fast-moving water carries contamination with it, allowing for less time for chemical break-down. Furthermore, if water moves quickly the porosity of the rock is often higher, and just as a filter with larger holes catches less stuff, the rock with larger pores filters out fewer contaminants. So, in areas where groundwater seems pretty plentiful due to good recharge rates, the groundwater is most susceptible to contamination. We’re seeing the results of this now in Central and Southeast Minnesota (Provinces 4 and 3), where nitrate levels above the federal drinking water standard are forcing private well owners and municipalities to invest in expensive technology to make their groundwater drinkable.

Central and Southeast Minnesota may also be the canaries in the coal mine when it comes to groundwater contamination. Because groundwater moves slowly, we will not notice contamination in deep wells immediately, but once groundwater is contaminated, there is little we can do to address the problem in the ground. Even if the source of contamination is cut off, it can take years for the pollution to “work its way out of the system,” and nearby well owners may continue drawing up polluted water for quite some time.

When aquifers are confined, as is common in Provinces 1, 2, and 3, a confining layer can prevent or significantly slow the spread of contamination in one direction or another. However, this just means that contamination will spread all the more readily to another water user tapping the same confined aquifer.

Availability

It’s also important to remember that while some parts of the state have plentiful groundwater supplies, others are running dry. Even in the Twin Cities, which, based on the characteristics of groundwater Province 1, should have plenty of groundwater, the low levels of White Bear Lake indicate that this might not be the case. However, rural reaches of the state with much lower population density are feeling the stress as well. In Western Minnesota’s Province 5, the combination of bedrock with water available only locally in limited fissures and cracks and clayey surficial deposits that yield poorly make finding water difficult. Marshall, for example, is spending $13 million to develop a 27-mile pipeline to bring water to town. The smaller town of Mountain Lake has a similar plan: after several test wells closer to home turned up useless, the city plans to invest half a million in digging a new well farther away and piping the water in. And some towns haven’t been able to find water resources close to home at any cost—and instead are looking to import it from South Dakota via the Lewis and Clark Water Project.

Regardless of what issue seems most important in your region of the state, anyone who uses water needs to also be thinking about groundwater. Each of these challenges will require unique and thoughtful approaches to ensuring a sustainable supply of clean water. We will explore our impacts on and solutions to these issues in more detail in the following posts.

Summary of Why Should I Care?

Groundwater directly affects our use of water in several ways, and an understanding of groundwater science helps to clarify those issues. Groundwater is critical to maintaining consistent water levels in surface water bodies, and knowing about the slow rate of flow of groundwater helps to explain why. Adequate infiltration and recharge of groundwater during rain events is also important when it comes to maintaining consistent water levels. Because recharge is highest in areas where the aquifers are permeable, areas that are good for recharge are bad when it comes to contamination, as the spread of contamination is also related to aquifer permeability. Thought aquifers can act as filters, if groundwater is polluted beyond the natural filtering capacity of the aquifer, which is already the case in Southeast and Central MN, addressing the pollution becomes very difficult. Finally, in some regions of the state with geology that forms low-yielding aquifers, simply finding enough groundwater proves to be a challenge. None of these problems are insurmountable, but they will require creative and thoughtful solutions.

Groundwater directly affects our use of water in several ways, and an understanding of groundwater science helps to clarify those issues. Groundwater is critical to maintaining consistent water levels in surface water bodies, and knowing about the slow rate of flow of groundwater helps to explain why. Adequate infiltration and recharge of groundwater during rain events is also important when it comes to maintaining consistent water levels. Because recharge is highest in areas where the aquifers are permeable, areas that are good for recharge are bad when it comes to contamination, as the spread of contamination is also related to aquifer permeability. Thought aquifers can act as filters, if groundwater is polluted beyond the natural filtering capacity of the aquifer, which is already the case in Southeast and Central MN, addressing the pollution becomes very difficult. Finally, in some regions of the state with geology that forms low-yielding aquifers, simply finding enough groundwater proves to be a challenge. None of these problems are insurmountable, but they will require creative and thoughtful solutions.

Blog post by Ariel Herrod, Watershed Sustainability Program Coordinator.