500 Years

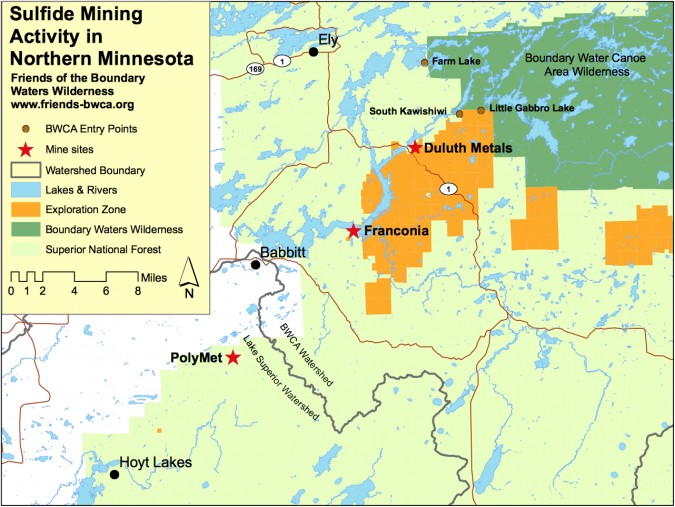

PolyMet Mining Corp. has offered Minnesota a Faustian bargain in the form of a sulfide mine in the Superior National Forest. The company has promised 20 years of jobs, economic stimulus, and the revival of the mining economy of Northern Minnesota through the extraction of copper, nickel, and other metals. An open-pit mine and prosperity. Oh, and 500 years of toxic waste clean-up.

Why Sulfide Mining is Worse

It is true that Northern Minnesota’s culture is rich with the history of mining, but sulfide mining is new, and it is different from iron ore mining in one major way. The copper and nickel are bound up in rock that also contains sulfide, which, when exposed to water and air, produces sulfuric acid. In order to get to the desirable minerals, PolyMet will also have to pull out and set aside the waste rock—the current plan is to create 20-story rock towers to store it. This will give the sulfide plenty of time to react with air and water, produce sulfates and sulfuric acid, leach heavy metals, and contaminate unknown amounts of water. In particular, high concentrations of sulfates in the water may spell doom for the native wild rice populations in the area. The potential for contamination is far worse with sulfide mining than it was with iron ore mining.

Regardless, PolyMet has promised to contain (almost) all the water from the mine site and the processing site—this includes even the rainwater that falls on the aforementioned toxic rock piles—and to clean that water using reverse osmosis. The estimate is that it will take at least 500 years to suitably purify all the water to the point that it can be released back into the environment.

And in 20 years?

Northern Minnesota has been caught in the bust part of the “boom and bust” cycle of mining economies for decades, and the support for the prospect of economic development is understandable. But we have to ask if this is just another 20-year boom followed by a 500-year bust, one that will leave the children of PolyMet’s miners returning home from college only to find that their hometown is struggling once again.

For more information on the proposals and the effects of sulfide mining, visit:

- Friends of the Boundary Waters Wilderness

- Conservation Minnesota

- Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy

- MPR

- Sierra Club North Chapter

A special thank you to MPIRG UM Morris for raising awareness of this issue in Western MN.